Table of Contents

NIST already recommends biometrics

Newsflash: passwords are generally awful at both usability and security. Historically, the band-aid solution has been to follow best practices from organizations like NIST (The National Institute of Standards and Technology). NIST is the authority that sets the gold standard for digital security practices in the US, though the institute dramatically influences global policies as well.

You might be familiar with some of their old-school password tips, like creating new passwords at regular intervals and using lots of obscure characters—advice that the original NIST author regrets publishing back in 2003. Since then, we’ve seen that these policies inadvertently lead to worse passwords that are harder to remember and easier to crack.

Notably, NIST hasn’t recommended either of these tactics in quite a while, but the reach of this unfortunate advice spans over two decades. Many organizations still enforce ideas their originator calls “barking up the wrong tree.” But there’s a silver lining, thanks to NIST updating their password recommendations. The institute just concluded the public comment period for its latest Digital Identity Guidelines, SP 800-63-4, meaning a complete publication is just around the corner.

We’ve outlined the top changes NIST is planning below. By the end of this article, you’ll be caught up on the most critical and impactful password policy recommendations recently published by NIST, and you’ll be ready for the next wave of guidelines.

NIST already recommends biometrics

Before we dive into the proposed update, you should know that NIST already recommends getting away from passwords as much as possible. In fact, NIST’s auth-focused companion document from August 2024, SP 800-63B, encouraged companies to embrace biometric methods such as passkeys. If you’re not familiar with passkeys, they’re based on FIDO2 (Fast Identity Online), a framework that allows highly encrypted key pairs to handle auth instead of memorization or password managers.

You can learn more about passkeys and how they work in our comprehensive guide.

The current guidelines also recommend organizations defend against credential stuffing attacks by enforcing blocklists for commonly cracked passwords, like “password,” “1234,” “admin,” and so on. Organizations that want to implement these blocklists might need to draw on external sources for breached passwords (like Have I Been Pwned), which can be tough to integrate without strong auth infrastructure in place. That’s why Descope offers a simpler way with a library of connectors—including an integration with Have I Been Pwned.

The next update reiterates these points, but it also looks loaded with common sense advice to protect users with smarter password policies. These include tips like not showing password hints to unverified parties (which seems like a no-brainer) and eliminating out-of-wallet questions (e.g., “What was the name of your first pet?”). Some of these are a bit obvious, but others are a welcome relief from that long-held, old-school mentality.

Simplifying password complexity

Ever notice how creating a password feels like solving an equation? Use this many characters but not more than that, at least one symbol, no number sequences—you know the drill. Mercifully, NIST is ending that headache, and gone are the days of mandatory special character soup.

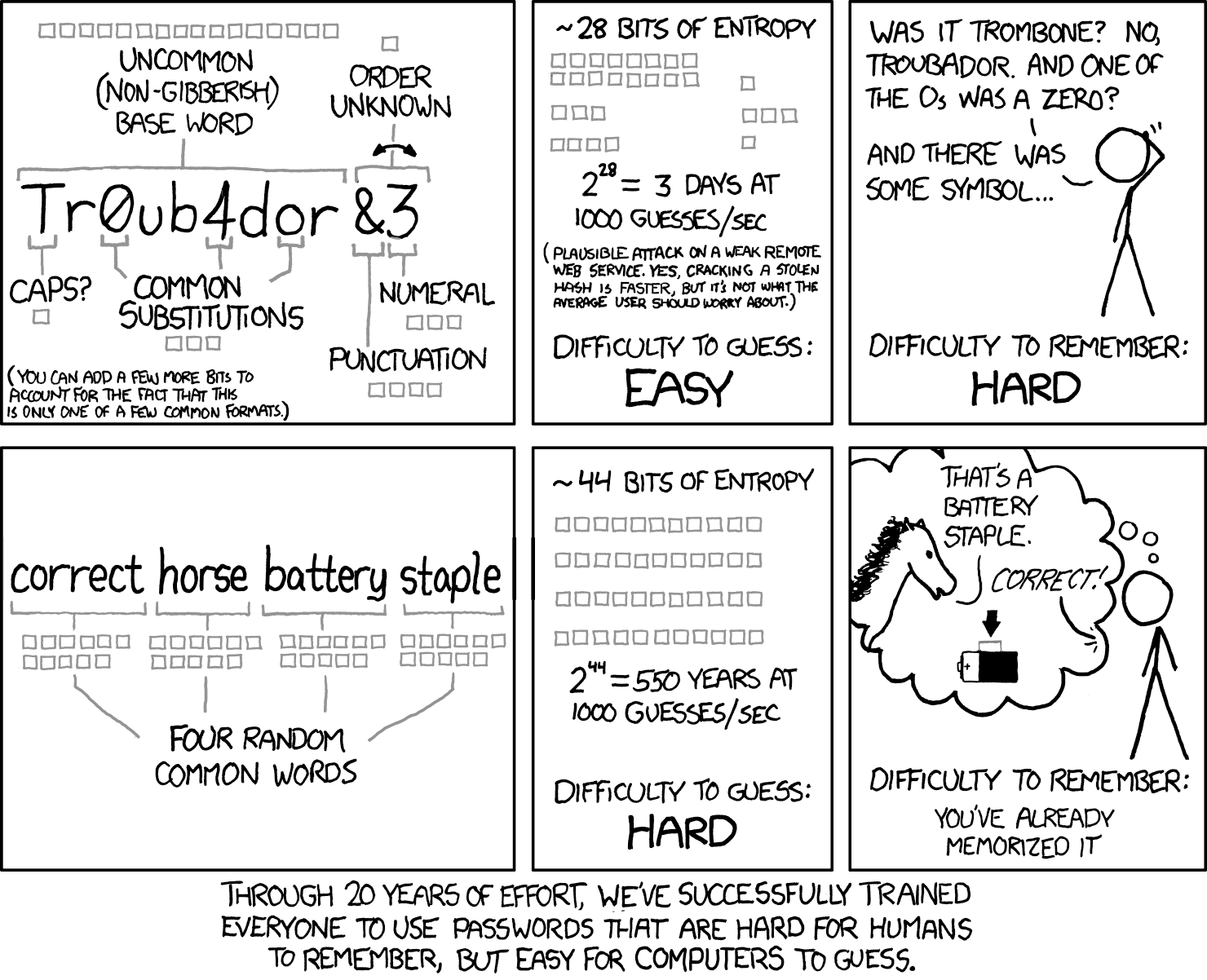

The painful reality about those cryptic complexity requirements is that they frequently backfire. Most users resort to predictable (read: guessable) patterns when forced to use a mix of uppercase, lowercase, numbers, and symbols. This results in passwords that are tougher to remember but simpler for machines to crack.

This strip below, from the webcomic xkcd, illustrates the concept:

As NIST puts it, “Analyses of breached password databases reveal that the benefit of such rules is not nearly as significant as initially thought, although the impact on usability and memorability is severe.” In other words, pushing for highly complex passwords results in highly unmemorable and unusable passwords.

So, requiring mixtures of different character types (i.e., upper and lower case, symbols, numbers) is out. What does NIST recommend now? Just like the comic above suggests, longer is stronger. They're advocating for extended passphrases that are easier for humans to remember but harder for machines to guess. NIST says the bare minimum is 8 characters, though they recommend at least 15.

NIST also advises organizations to support up to 64 characters, which might sound like a lot, but is music to many security conscious users’ ears.

Saying goodbye to periodic password changes

If you've ever groaned at the "Your password will expire in 3 days" notification, you're in for a treat. Older NIST recommendations are why you may have been obligated to change your work passwords, adhering to a strict moratorium on repeats. Yet, humans don’t work like that—we prefer to keep things simple (and less secure).

Contrary to cybersecurity myth, frequent password changes often decrease security. When forced to create new passwords every few months, users tend to make minimal, predictable alterations to their existing passwords. "Winter2024!" becomes "Spring2025!", which is not exactly a security upgrade (even if the interface assures you it’s “strong”).

Because of trends like this, NIST is actively recommending against frequent password changes. But that leaves us with a question: If they pulled the plug on mandatory periodic password changes, when should you ask users to switch things up?

Simple: update only when there's evidence of compromise. It's a more targeted, effective approach that doesn't unnecessarily burden users… or drive them to create the worst passwords imaginable.

Embracing the full character set

NIST is giving users the keys to the character kingdom. They're encouraging the use of ASCII and Unicode characters in passwords, which might sound like tech jargon, but simply means you can use pretty much any character your keyboard can type. This includes everything from standard letters and numbers to characters from other languages. You can even use the trademark or copyright symbols on your passwords, although it’s doubtful if they’d hold up in court.

While it may seem like another step to introduce even more complexity, remember that NIST has recently de-emphasized complicated passwords in favor of length. Here, it’s not about stacking tons of fancy characters into every password—it's encouraging organizations to support more user choice by removing arbitrary restrictions. Too many services still limit users to basic characters, but NIST is saying it's time to crack open the alt code handbook.

The move also aligns with how people actually use computers in 2024. We communicate in GIFs, emoji, and characters from dozens of languages. Our password policies should reflect this reality rather than hanging onto arbitrary restrictions from the dial-up era. Though if you're thinking about using nothing but emojis for your next password, maybe pump the brakes on that idea.

Passwords are here to stay… for now

How many passwords do you have? According to NordPass, the average user clocks in at 225. While clever you may have hit the “Create a strong password for me” button in Google Chrome for every single account, cheerfully offloading the task of remembering a password to your browser, there are still hundreds of passwords associated with your online identity—and hundreds of attack vectors for would-be cybercriminals.

This brings us to the crux of NIST’s password guideline update: The underlying problem of password authentication remains. While NIST's most recent publications encourage the use of biometric authentication, and the proposed update is a step in the right direction, they're not going to “fix” the inherent weakness of passwords. No amount of special characters or length requirements will change that fundamental flaw.

Even so, the real challenge is getting organizations to actually implement these guidelines. After all, we're still seeing mandatory password rotations and complexity requirements that NIST hasn't recommended in years. But at least this new proposal makes the password burden a little lighter.

It’s based on how humans actually behave, not how we wish they would behave. And that's progress, even if it's not the final destination.

We hope you enjoyed reading this blog and found it useful. For more auth news, subscribe to our blog or follow us on LinkedIn.